Blog

NOVEMBER 30, 2020

It’s Not You, It’s Me

When thinking about what I wanted to say for this week’s 45th Parallel Universe blog, I was tempted to write a rather salty take discussing classical musicians’… let’s call it “occasional” failure to present contemporary music and lesser-known works from the classical canon with the same stylistic imagination and rhetorical commitment with which they would approach, say, a symphony by Brahms. BUT, it’s the holidays… during a pandemic… after a divisive election… and we are talking about an extremely subjective art form. Add in the fact that I am painfully aware of my own musical shortcomings, and maybe it’s best if I (mostly) restrain myself.

My latest round of rumination on performer responsibility was kicked off by preparing the repertoire for the next Portland Social Distance Ensemble live stream scheduled for Friday, December 4th. The program features two relatively lesser-known works: a trio for Clarinet, Cello, and Piano by the French Romantic pianist and composer Louise Farrenc, and a Quartet for Clarinet, Violin, Cello, and Piano written in 2017 by the mind-bendingly original Andy Akiho.

Farrenc’s Trio in E♭, Op. 44 (1854–56) is an absolutely stunning work which in many ways outshines Beethoven’s better-known trio for the same instrumentation. I first performed the work just a few months ago, and I’m now embarrassed that I didn’t play it sooner; this work deserves a place in the repertoire alongside trios by household names like Beethoven and Brahms. Farrenc no doubt suffered from the sexism embedded into the cultural fabric of her day, and that is sadly a force that persists in our current moment.

One barrier for relatively lesser-known classical and romantic composers is the dearth of good reference recordings. While performers should be thinking for ourselves and coming up with our own convincing interpretations, it’s useful to check out YouTube or iTunes to hear how performers from different periods of the recorded age solved particular challenges and crafted a convincing performance. A performer tackling a Beethoven quartet knows whose fault it is when their performance is less than captivating; a wide variety of successful counter-examples exist and can be easily located on the internet in a matter of seconds. With lesser-known works, it is often harder to find a sparkling rendition which, while perhaps not to your own personal liking, can clearly demonstrate that this is a piece worthy of your time and energy, even if you might initially lack the imagination and familiarity to see it. Many times I’ve had the experience of rehearsing an unfamiliar piece while thinking “well, the 4th movement is ok, but the others are duds,” only to find after a little effort and creative thinking in subsequent rehearsals that, in fact… it was me. The responsibility of the performer must always be to ask “how do I make this work come to life in a way that will captivate the audience and stir their imagination and emotion?” Tackling compositions by lesser-known composers can expose shortcomings of interpretation even more clearly than canonical works, particularly those composed in a style that classical musicians ought to be somewhat familiar with. Trevor, Maria, and I will do our best to present Farrenc’s marvelous Trio with the care and nuance that it warrants, as this is a work that deserves the attention of chamber music aficionados.

Interpreting works from the past 100 years presents a different set of challenges. An extremely wide range of styles fall under the silly but sometimes unavoidable categories of “Modern” or “Contemporary Classical Music.” Works by Arnold Schoenberg, Copland, Glass, or Saariaho might require radically different approaches compared to each other, or to Mozart for that matter. But then again… sometimes they might not? I once attended a sadly uninspired performance of John Adams’ “Naive and Sentimental Music” by one of America’s most storied orchestras. At one point I glanced at the cello section as they approached what I considered to be a beautifully expansive melody. I was disappointed when the musical line was rendered as string of seemingly unrelated and indifferent tones, as though the task of performing this music was a tiresome bore. Needless to say, the audience left in droves after the first movement, and more followed after the second. I’m not sure if a more committed performance would have mattered for the relatively conservative audience in attendance, but this was a massive neo-romantic work from one of America’s leading composers, whose music is widely considered to be accessible. At the bare minimum it stands out in my memory as one of the more unfortunate “missed opportunities” in my concert-going life.

In spite of any number of unique challenges that contemporary music can present, from complex rhythm to extended instrumental techniques, these are still works that deserve as much attention to color, nuance, balance, and style as anything from the classical or romantic eras. Andy Akiho’s Quartet Lost on Chiaroscuro Street almost seems to hint at as much in the title. This five-movement work explores a wide range of textures, from the static to the frenetic. Fitting of his instrumental background as a percussionist, Akiho’s handling of rhythmic material stands out for its toe-tapping complexity and buoyancy. This is music that needs to groove, no matter how much higher level math is required to count it correctly! The five movements of the work form a sort of palindrome, the opening “prelude” making a shadowy return in the closing “postlude.” The 2nd and 4th movements offer prime examples of Akiho’s trademark rhythmic style. Like Messiaen’s similarly scored Quartet for the End of Time, Akiho’s Quartet includes a haunting movement for solo clarinet, which occupies the central point of the structure.

Both of these works, composed in the mid-19th c. and the early-21st c. respectively, deserve a place in the repertoire. With less-familiar works, especially those from composers who are often discriminated against consciously and unconsciously in classical music’s sadly white male-dominated culture, musicians need to be particularly wary of their own preconceptions. Embracing a default assumption of “it’s not you, it’s me” when rehearsing these works is key. To some extent, that should always be our job – to use our imaginations and fill in the nooks and crannies created by a limited notational system, and ensure that we create the most luminous performance within our abilities. That should be our commitment to composers, audiences, and ourselves alike, and with overlooked composers of the past and emerging composers of the present, that oath should be all the more sacred.

James Shields

Principal Clarinet, Oregon Symphony

Don’t forget to share this post!

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE…

Ewer, Always On My Mind

Lisa Lipton recently interviewed Greg Ewer, founder of 45th Parallel and member of the Pyxis Quartet, about the Friends of…

Anatomy of a Concert

“Check out this amazing piece by Andy Akiho!” I can’t remember who sent that text to me, though it was probably one my fellow music geek buddies…

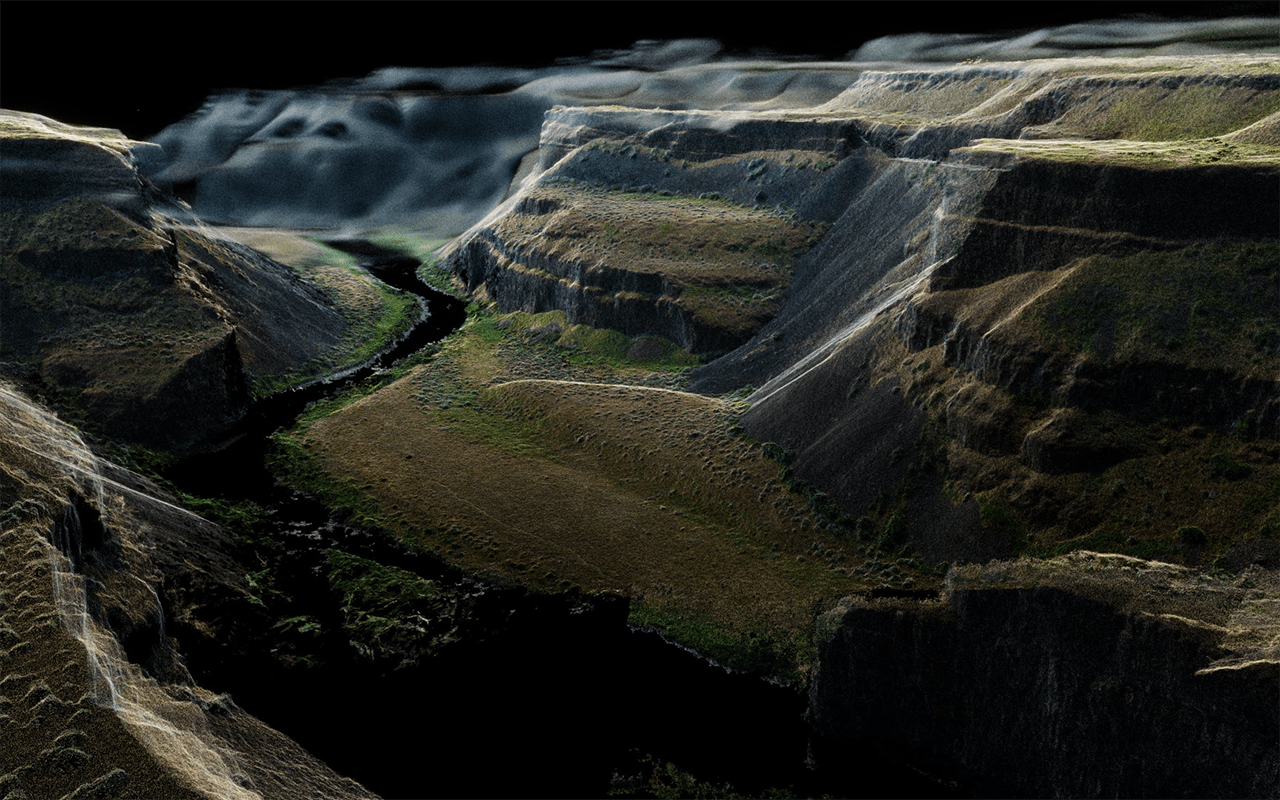

Lisa Interviews Geologist Dr. Scott Burns

Executive Director Lisa Lipton met with Dr. Scott Burns, Professor Emeritus at…